Is Artificial Intelligence Intelligent?

David BauThe idea that large language models could be capable of cognition is not obvious. Neural language modeling has been around since Jeff Elman’s 1990 structure-in-time work, but 33 years passed between that initial idea and first contact with ChatGPT.

What took so long? In this blog I write about why few saw it coming, why some remain skeptical even in the face of amazing GPT-4 behavior, why machine cognition may be emerging anyway, and what we should study next.

Spark-Jones’s worry about language modeling

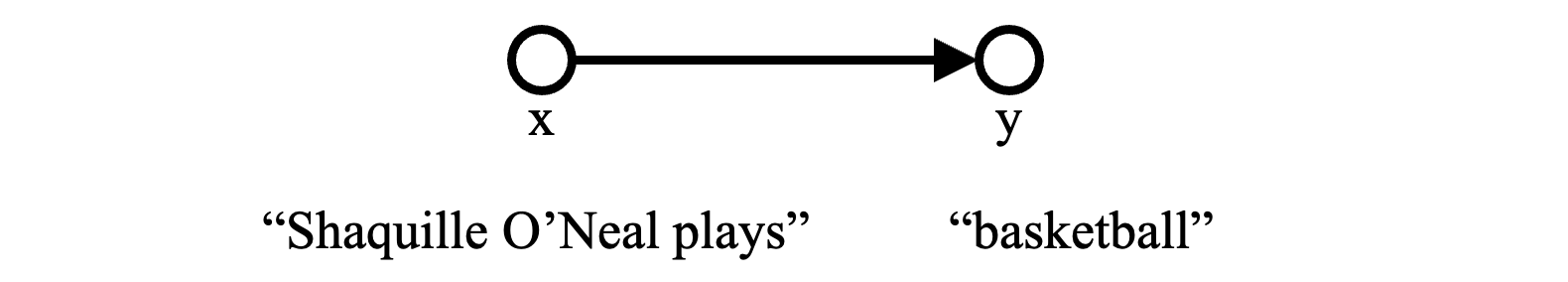

This blog was inspired by Karen Spark-Jones’ 2004 note that asks whether the generative model for language modeling is rational or not. In it, she points out that language models (such as GPT) are based on a highly implausible statistical model of the mechanisms of language, like the one depicted here:

The reason this picture seems so unlikely to lead to a rational model of intelligence is that nobody actually believes that words cause other words! This graphical model is just a shorthand for expressing the assertion that the probability distribution of y depends on nothing else but the observation of the previous words x. When critics note that LLMs are mere stochastic parrots, warning of the false promise of ChatGPT, the implausibility of this picture is at the root of their argument. Words do not spring from other words. But that is the basic assumption that language models make.

Consider the example of the Turing-test-contestant programs such as ELIZA, ALICE, Jabberwacky, Cleverbot and Eugene Goostman. These are structured like the graphical model above, imitating human conversation by choosing textual responses based on statistics and pattern-matching on previous words. Nobody, not even the creators of those systems, seriously believes that the design of such pattern-matching engines contains profound cognitive capabilities. They are parlor tricks, automata that display a shallow semblance of intelligence while just following simple procedures.

Yet, somehow, though ChatGPT works the same way, it seems more profound. What is the difference? Is ChatGPT the same as Jabberwaacky; separated only by scale, a few years of Moore’s law, a big budget, and slightly better programming? Or if they are substantively different, what is the fundamental difference? What line has been crossed?

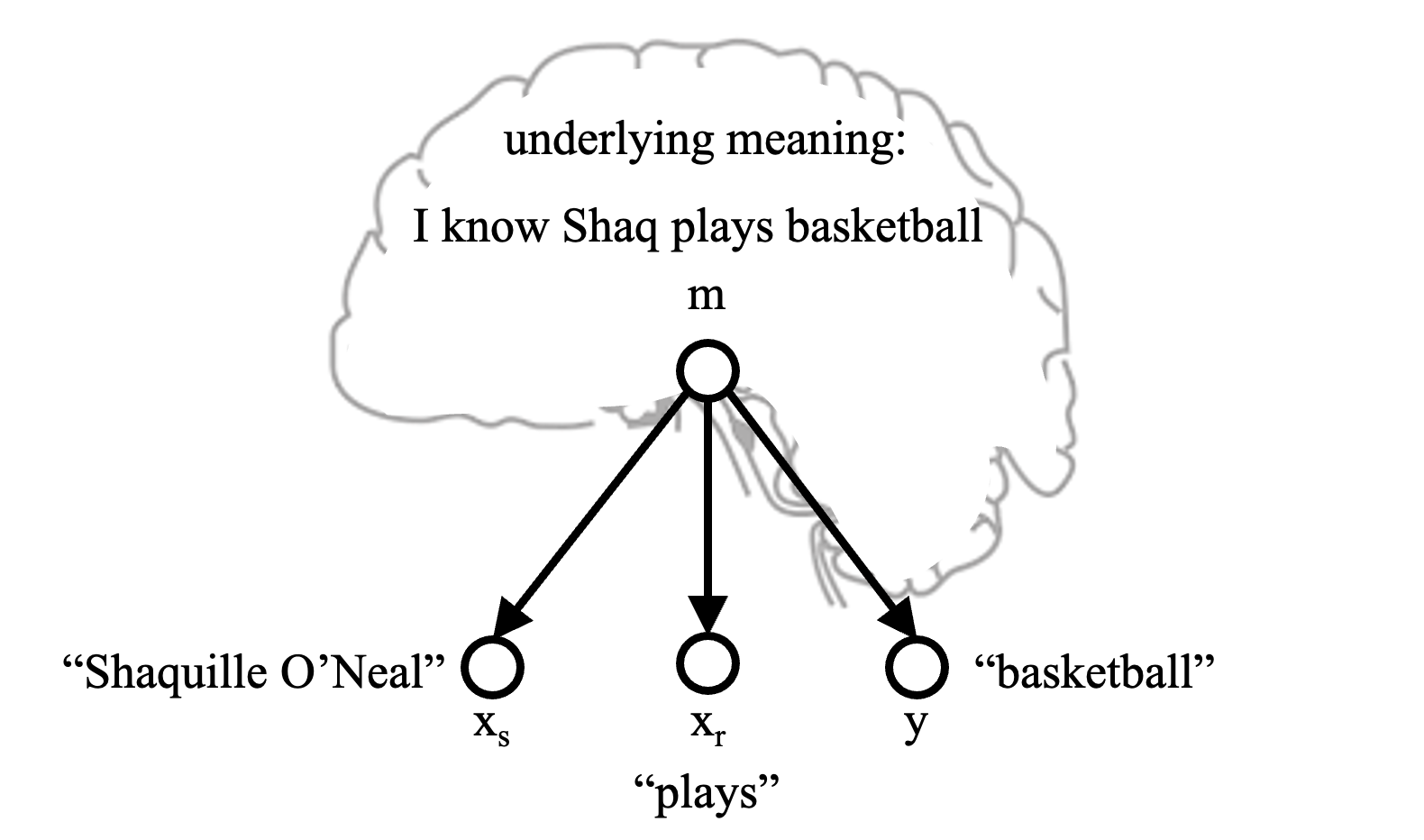

To appreciate what Spark-Jones found to be missing in the traditional language modeling view, contrast the diagram above to the following graph that provides a more rational model for the cognitive process of language.

Spark-Jones drew graphs like this to indicate what we are really after. Here the “m” denotes the underlying meaning that exists within your mind, causing you to utter the words “Shaquille O’Neal plays basketball.” This model is more plausible, because it is not words that generate other words, rather, it is our thoughts, knowledge, intentions and desire for expression that cause words to be spoken.

GANs have the right shape but cannot do language

Before you object that such an imaginative abstraction is unrelated to practical considerations in the field of artificial neural networks, keep in mind that it is common to create neural architectures with an explicit state vector that plays the role of m. For example, contrast Pixel-CNN networks, which model an image by predicting each pixel as a consequence of previously-seen pixels above and to the left, with generative adversarial networks (GANs), which use an explicit representation stored in a small hidden state z that predicts all the pixels, with no upstream dependencies.

Both architectures are able to synthesize realistic-looking images of the world. However, it seems very unlikely that the Pixel-CNN architecture would contain any sensible representation of the world, because nobody believes that pixels cause other pixels.

![]()

On the other hand, the GAN architecture seems more promising, because it posits a set of variables z that are the cause of all the pixels. In a GAN, we are hoping for z to represent “state of the world” and “state of the camera,” and for this state to lead to a reasonable set of calculations that produce the image of a realistic scene.

Remarkably, with this setup, GANs show evidence of learning rational models of the world. If you are unfamiliar with GANs, I recommend reading Karras’s StyleGAN papers and then the StyleSpace paper from Wu. Wu found that there is a small set of bottleneck “stylespace” neurons within StyleGAN that correspond to real-world concepts such as whether a person is wearing glasses or whether they are smiling. The results are empirical, but the phenomenon has been observed in various GAN models trained on different data sets.

When we reproduce Wu’s results on a GAN trained to draw bedrooms, we find a single individual neuron that controls whether the lights are turned on or off. There was no explicit supervision that led to this disentangled neuron being learned: the GAN was just trained on individual images and never saw a video where a light was switched. But for some reason, the learned model arrived at a solution where there is a distinctive “light switch” neuron that imitates the action of a light switch in the real world.

So rational graphical models seem to be a promising path for possibly learning reasonable models of the world, maybe even reasonable models of cognition. Unfortunately, GANs and similar architectures have not (yet) been successful at modeling anything as complex as natural language. That might be because the cognitive processes that lead to language are too intricate for these architectures. Ultimately, humans draw upon an enormous amount of knowledge just to conjure up a simple utterance.

Transformers have the wrong shape but may harbor knowledge

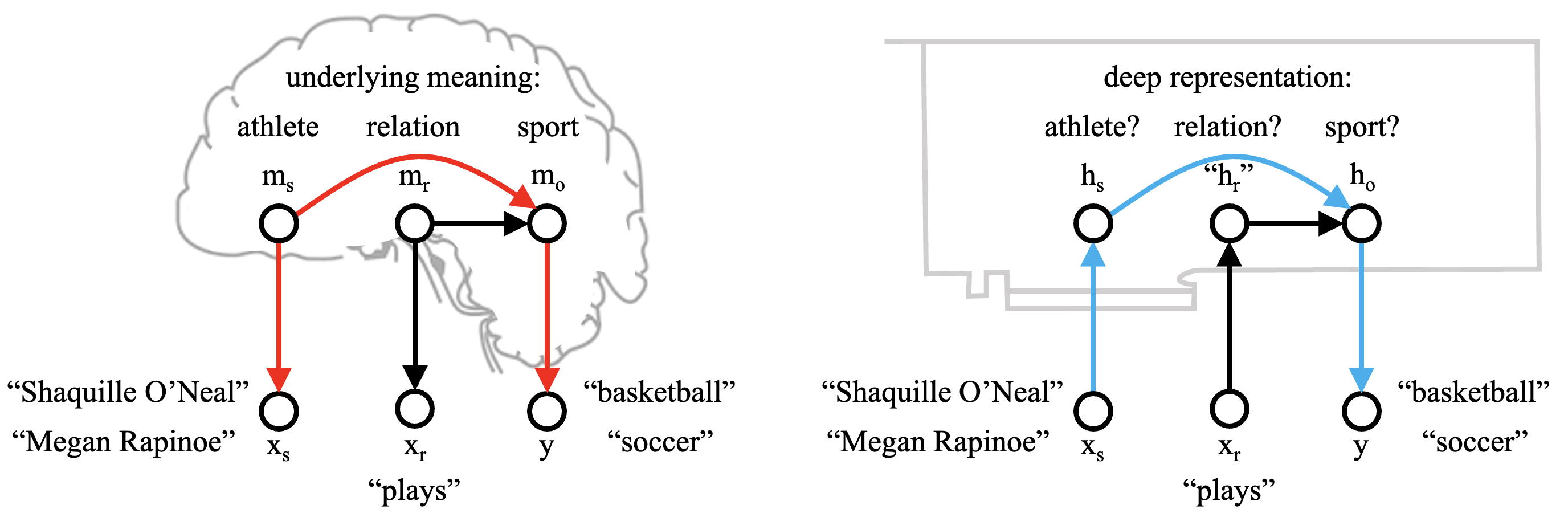

Consider the sentence “Shaquille O’Neal plays basketball.” Although the words “soccer” or “tennis” are often reasonable alternatives to the word “basketball,” when talking about Shaq playing basketball, other sports cannot be substituted in that particular sentence.

This is because the sentence is not just making a grammatically correct statement. The sentence reflects a humanlike thinking process: it reflects our knowledge about Shaq. We would only say “soccer” if we meant the sport of a soccer player like Megan Rapinoe, or if—for some reason—we pretended to hold the mistaken belief that Shaq played soccer. A decomposition of the individual ideas within our mind might be diagrammed like the figure on the left.

Unfortunately, autoregressive models have the “wrong” top-level structure to directly implement the model on the left: in an autoregressive transformer, preceding words are inputs rather than outputs.

On the other hand, research from my lab by Kevin Meng et al. (ROME) suggests that transformers can implement reasonable models of cognition by learning explicit hidden states that carry information about a meaningful facet of the world. The graphs end up looking like the picture on the right, with the same structure as a rational model with some arrows reversed.

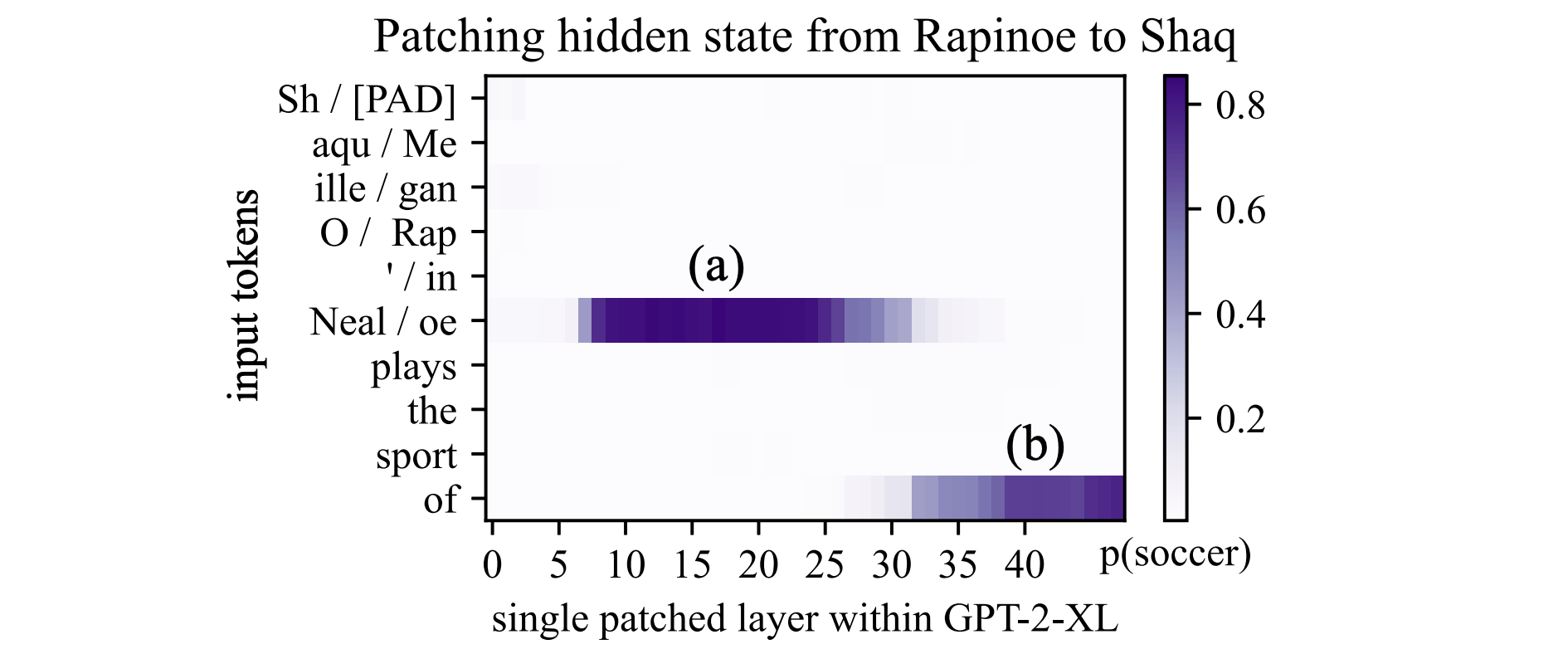

Consider the plot below, which shows the effect of swapping individual hidden states between two runs of a GPT model, one with a sentence about Shaquille O’Neal, and another with a sentence about Megan Rapinoe.

Ordinarily the sentence is about Shaq and predicts “basketball.” But if we take a single hidden state from Megan’s sentence and move it over, then at some locations (shown in purple), it will cause the model to flip its predictions to “soccer.” It is unsurprising that swapping states late in the model, at (b) will cause this effect, but the surprising finding is that a small set of states deep within the model, at (a), also cause the model to flip its predictions.

In the ROME paper we find evidence that these early states correspond to the point at which the model retrieves its knowledge about which sport the athlete plays. For example, if we intercept and modify the parameters of the model in the early site (a), we can edit the model’s belief and make it think that Shaq plays soccer.

Kevin’s interpretation of the causal structure within the network is pretty effective. In his MEMIT paper, he finds that he can use his understanding of the structure to directly edit transformer memories at scale, providing control over transformer memories that is several orders-of-magnitude better than traditional fine-tuning methods.

The emergence of reasonable “world models” inside large transformers, despite the reversed direction of the arrows, has been observed in several other works that are worth reading about. Be sure to read the Othello paper by Kenneth Li, et al., as well as Neel Nanda’s followup. Read the induction heads paper by Catherine Olssen, et al., the Alchemy paper by Belinda Li, et al., and the indirect object identification work by Kevin Wang, et al. All these works reveal little pieces of a secret:

Transformer models do not just imitate surface statistics. They go beyond that, often constructing internal computational mechanisms that mimic causal mechanisms in the real world.

Beyond the Turing Test

A decade ago, Gary Marcus argued that we need to move beyond the Turing test as our metric for the emergence of machine intelligence. He observed that the test is too easy, that humans are too easily fooled by the mere appearance of intelligent behavior. He argued that a true intelligent agent would contain rational thoughts, that would allow them to understand actual relationships and motivations and causes in the world rather than mere word statistics. At the time, Marcus gathered together a series of more difficult tests of behavior, such as open-ended questions about movies and stories, questions about theory of mind, motivation, desires, and problems that seem to demand an understanding of the world such as visual question answering.

Yet now a decade later, just when large language models are beginning to solve all these more-difficult tasks, Marcus continues to meet the results with skepticism, observing that the massive scale of training data might still be fooling us. He points at flaws in logic and knowledge as evidence that the models are not really thinking.

But there is an obvious gap in Marcus’s current objections. Is perfect logic and complete knowledge a prerequisite for “thought?” Certainly most of us human beings are not capable of total factual recall and flawless logical reasoning. Today, Marcus’s solution for the dilemma seems to fall short.

The apparent need for an endless escalation of more-difficult external tasks for probing cognition suggests that Turing’s basic framework has been missing an essential point. In 1950, Turing proposed that we do not care about the implementation of a machine intelligence. However, today it is becoming increasingly clear that fooling an external judge is not enough. We do care what is inside the box.

The mechanistic-interpretability research program shows a way out of this trap. Instead of suggesting ever-more-difficult external tests of behavior, it aims to develop experimental methods that tear back the curtain on black-box-models, asking “what does a model learn?” by uncovering the forms of computation the model contains, and asking whether those computations capture useful, meaningful, and causal structure about the world.

We are in early days, and this new research program is very immature. We do not yet have abstractions that describe what it is that we are doing in a satisfying way. But as the world grapples with the emergence of surprising intelligent behavior in large models, the detailed study of mechanisms within those models will become increasingly important. A study of machine-learned mechanisms offers a new path for understanding what our big computers are really learning.

Footnotes and responses

Some other things worth reading that are related to the ideas here: Ferenc Huszár wrote a very interesting contemplation of other reasons he missed the promise of LLMs, including the No Free Lunch theorem, and his own reasoning about the futility of maximizing p(data). On the optimistic side, Jacob Andreas’s Language Models as Agent Models paper hypothesizes that LM can model intention because they are models of the communicative intent of writers. Michael Jordan has a different take, arguing that the Turing test is no longer interesting because we should be setting our sights higher than mere imitation of humans!

After posting the above, I received the following throughtful responses.

Yonatan Belinkov writes:

- Next word prediction may appear irrational, but we should remember that it is a way to get the probability of any body of text via the chain rule. Ryan Cotterell recently made a comment on twitter reminding us that p(text) is a very strong thing. In a sense, maybe p(text) is all we care about, and next word prediction is just one way to get that p. It is also interesting to think about whether the autoregressive factorization is the preferred way for some reason.

- We must acknowledge that ChatGPT and similar models do more than next word prediction. First, their pre-training data sets are not just ordinary natural language. They are trained on code, and that gives them possibly external semantics via assertions. See this theoretical paper in TACL by William Merrill et al. Second, these models are fine-tuned on instruction data sets. Third, reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) is applied.

- We should also remember that there is a gap between linguistic skills and other non-language-specific cognitive capabilities that may be essential parts of human thought. Read the recent survey by Mahowald and Ivanova, et al.

- I am a bit cautious of our heat maps from ROME’s causal tracing given both the paper from Hase, et al as well as follow-on experiments from our own labs. I think the results are meaningful but perhaps the interpretation will ultimately be more subtle.

David’s responses to Yonatan:

- If there is any lesson from machine learning, it is that modeling p(data) is impressively strong as an objective; maybe it is the most complete way to express the Turing test. On the other hand, what I am suggesting is p(data) is just serving as a powerful pretext task. A rational algorithm implementing the model is the real goal, and that goal is not perfectly equivalent to matching external observations of p(data).

- Yes, in this blog narrative, I have swept implementation details of ChatGPT under the rug, and readers need to be aware that instruction-tuning and RLHF are being used, e.g., read Christiano, et al. To me, it seems that the language modeling pre-training is the “secret sauce” behind ChatGPT. Of course GPT-3+ models are closed and proprietary, so we can only guess, but it seems likely that the vast majority of training data and computation is spent on pre-training, and that the fine-tuning just imparts a final domain shift to prepare the model for dialogue. Thanks for the link to Merrill about the possibly profound importance of pre-training on code.

- Thanks for the link to Mahowald and Ivanova’s survey. They remind us that humility is definitely in order when comparing language models to the breadth of human cognitive capabilities. Nevertheless, I think we have all been impressed and surprised at how many seemingly non-linguistic capabilities have emerged from the language modeling task.

- In the end, I think our ROME findings about the organization of factual recall in transformers will be found to be robust—some explorations of various ways to stress-test the results are already included in our ROME appendix on arxiv, and of course the scalability of MEMIT is a powerful validation—although I agree, the picture should be clarified further, and more experiments in more settings and with more models will be needed.