Catching Up

David BauToday, I received an email from my good college friend David Maymudes. David got his math degree from Harvard a few years ahead of me, and we have both worked at Microsoft and Google at overlapping times. (David designed the video API for Windows and created the AVI format! And we both worked on Internet Explorer.) He is still at Google now.

From inside Google today, he is a direct witness to the transformation of that company as the profound new approaches to artificial intelligence become a corporate priority. It is obvious that something major is afoot: a new ecosystem is being created. Although David does not work on large-scale machine learning, it touches on his work, because it is touching everybody.

Despite being an outsider to our field, David reached out to ask some clarifying questions about some specific technical ideas, including RLHF, AI safety, and the new ChatGPT plug-in model. There is so much to catch up on. In response to David’s questions, I wrote up a crash-course in modern large language modeling, which we will delve into in this blog.

David’s first question was whether people control models by literally training the whole thing as a single black box. Or are there many boxes trained separately?

Yes, it is a monolith.

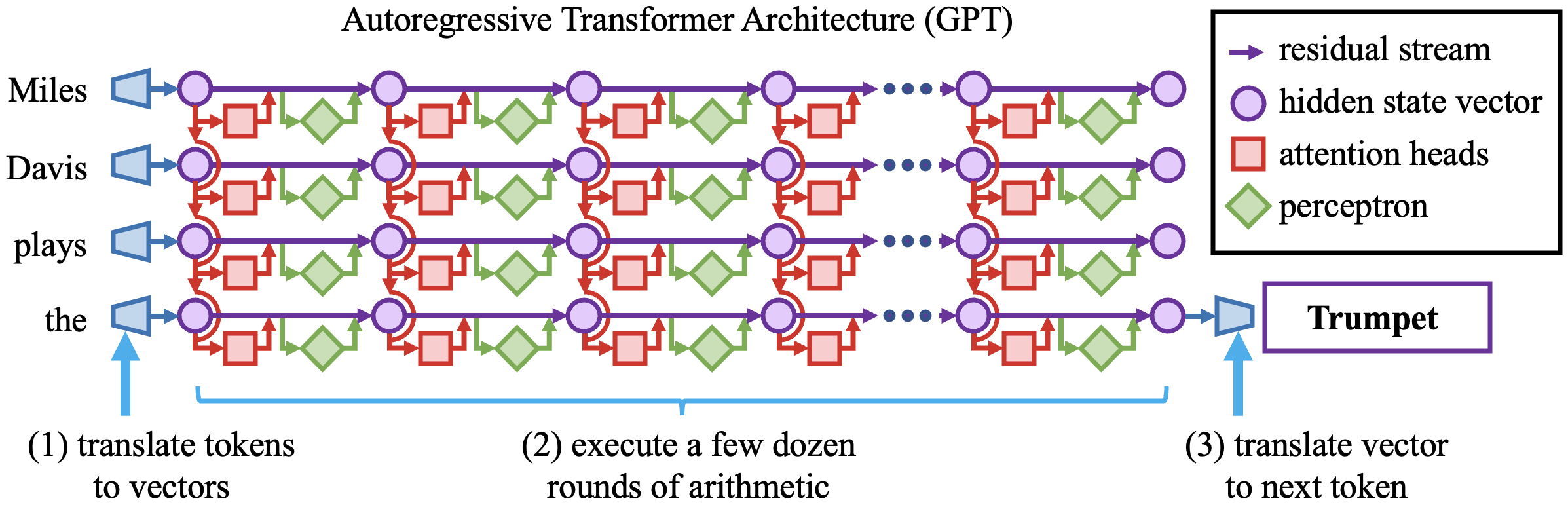

To implement a basic autoregressive (next-word-prediction) transformer model like GPT, we create a function that takes a sequence of words as input and produces the predicted next word as output. The output is actually a ranking of all the possible next words and their correct probability weights.

This function is implemented using a series of numerical steps.

- We turn each word fragment in the input into a vector of a few thousand numbers using a big lookup table, so that the whole sequence of input words will be many thousands of numbers: an array of “hidden state vectors.”

- We then execute a single, crazy big high-dimensional calculation that applies a few rounds of simple arithmetic to all those numbers in a few dozen parallel steps, with each step transforming each array of vectors to another array of just as many vectors.

- After the dozens of rounds of calculation, the final vector is read off the last layer of the output, and that vector is compared to a final output lookup table (listing a vector for each possible output word fragment) that determines the predicted next words.

At each step, every single number could in principle depend on every number of the previous step, but the exact dependencies are determined by an architecture that does lookups in big parameter tables. The size of those tables puts a ceiling on the complexity that can be encoded. For example, GPT-3 has 175 billion parameters, while the size of GPT-4 is unknown but estimated to be about a trillion parameters. You can think of these sizes as “the size of the interpreter that is processing the text.”

This word-prediction-as-vector-calculation idea is a very simple framework that was developed in the 1990s by Jeff Elman, Michael Jordan, Sepp Hochreiter, Yoshua Bengio, and others. What’s new in recent years is that we have found a good way to cleverly constrain the computations to impose some structure that reduces the complexity of the computation and improves parallelism in a very effective way. The structures that we impose on neural language modeling today are “attention heads” (a 2015 idea from Dzmitry Bahdanau) and “multilayer perceptrons” (credit Rosenblatt from the 1960s) and “residual streams” (due to Kaiming He in 2015). The way the pieces are put together is what people call the “transformer architecture” (devised by Ashish Vaswani from Google in 2017). All the gory details of transformers are explained beautifully by Jay Alammmar in his illustrated transformer series.

Transformers can be thought of as encouraging sparse data-associative wiring diagrams within all the calculations, and they have proven very effective at learning computational patterns that people might call intelligent. However, the computational paths that are learned within the transformer architecture form a tangled amalgamation of internal circuits that is opaque to us. We train it as a monolith to solve the very simple “pretext task” of predicting the probabilities of the possible next words as accurately as possible. The internal computational structure that emerges is very surprising, and that is the subject of the study of mechanistic interpretability.

Prompt engineering and in-context learning.

The idea that so many capabilities could be learned from the word-prediction task was not obvious to experts until very recently. Credit for some intuition goes to Alec Radford at OpenAI who pushed hard on scaling up autoregregressive transformers in the initial GPT work in 2018.

In a series of increasing investments in larger GPT models trained with more parameters on more text, Radford and his collaborators found that this simple architecture is a remarkable chameleon. For example, it quickly guesses the context, and if it thinks it is in the middle of a book of poems, it will use a strategy that leads it to generate more poetry. But if it sees context that looks like Javascript source code, it will generate realistic Javascript code. The same applies for a screenplay, spreadsheet, Reddit thread, parallel multilingual text, answer key for a test, output of a computer script, opinion piece, dialogue between two people, diary of internal ruminations, and so on. The extreme context-sensitivity seems like an oddball phenomenon, but it may be a linchpin that leads to reasonable models of cognition, as Jacob Andreas has convincingly argued.

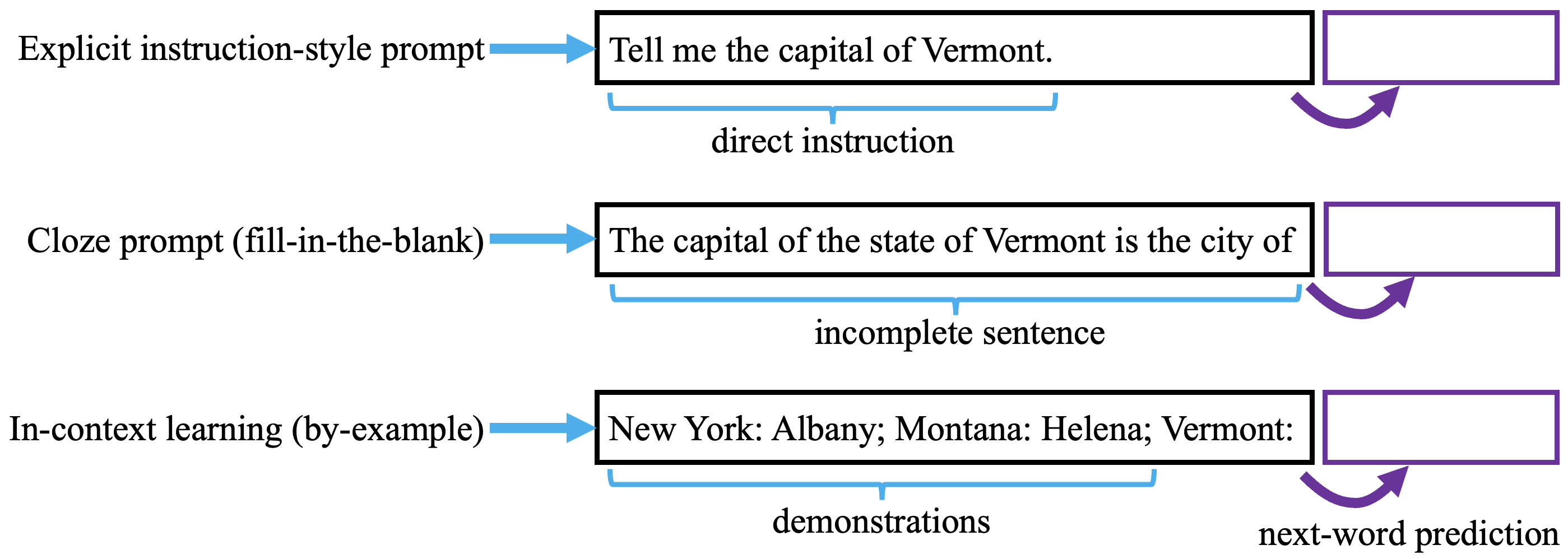

The observation of context-sensitivity has led to a flood of “prompt engineering” that demonstrates all the tricks you can do by setting up some clever input context for the model. For example, if you set up the input text to look like a standardized test, you can see how well the model can complete the answer key, and what is remarkable is that the large models contain real-world knowledge of facts and relationships, or even the ability to solve some math problems. With different prompts, it is stunning to see the model do things like translate between French and English when you prompt it as if it is working on parallel text, predict the output of a computer program given the code, write out step-by-step reasoning for some complex problem, or even follow instructions, e.g. “write me a poem,” and then it predicts that the best next words are a poem.

One of the most effective ways to create a prompt is called “in-context learning” where you give a handful of fully-worked examples the way that you’d like to see them done (starting with the problem and followed by the answer), and then you put the problem as the last example and ask the model to make its prediction. For complex problems, it works even better if you do it in a way that writes out the steps of the work explicitly in each demonstration; that is called “chain of thought” prompting.

However, it is more convenient for people when a model is able to solve a problem “zero shot,” i.e., with no worked examples shown at all. Some consensus is now forming that the most useful mode for these models is the “instruction-following” mode, where instead of requiring a few examples, you give it an explicit instruction like “Tell me the capital of Vermont,” and then it follows your request. Base pretrained GPT can follow instructions to some extent, but it often behaves as if it is unsure about whether it should actually follow the instructions or not. Perhaps after you give it an instruction, it cannot decide whether it is in a context where it should follow some other pattern, such as creating a list of many possible different things to do (it might follow with “Tell me the capital of Colorado”), or maybe continuing a story about the demands of a bossy character (“I bet you don’t know it”). Once in a while it might choose to actually follow the instruction.

That kind of uncertainty about context can be trained out of a model through fine-tuning.

Instruction fine-tuning and AI safety.

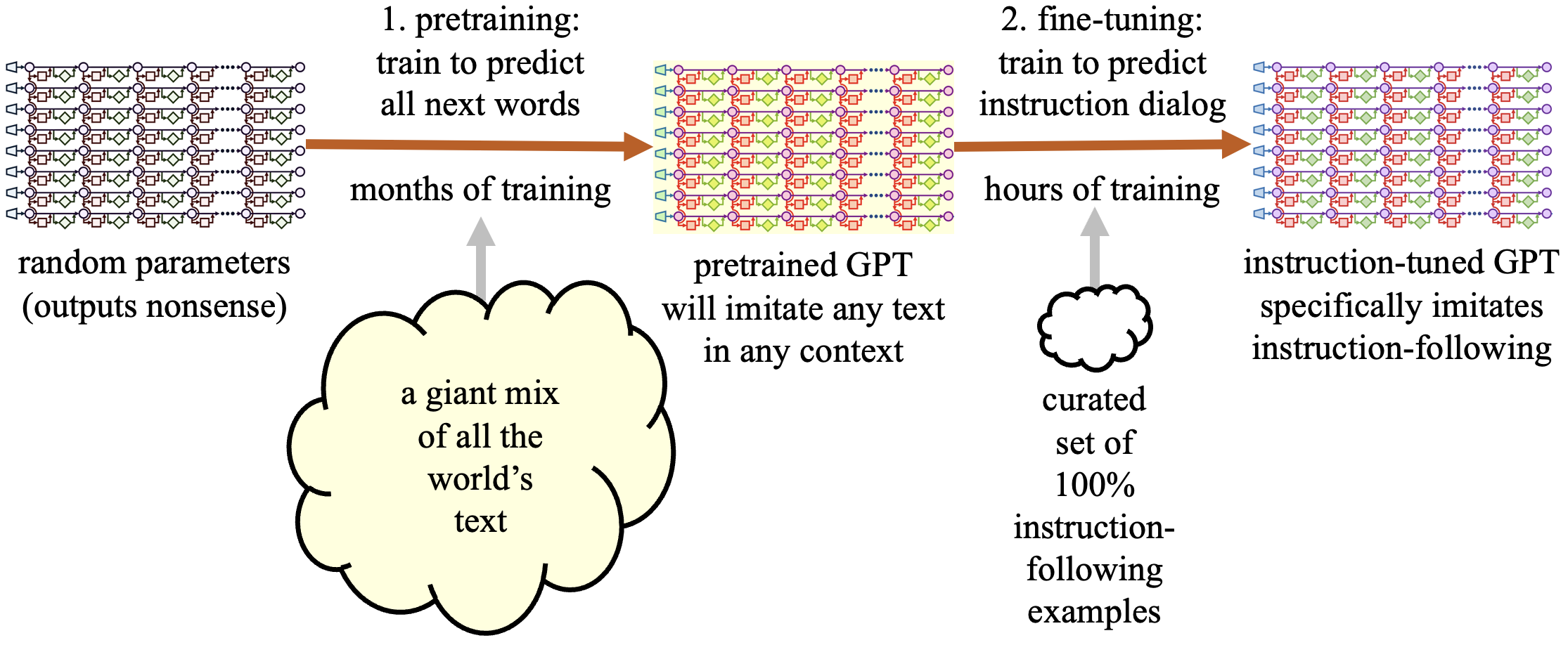

One of the main techniques in modern machine learning is transfer learning, which involves starting with a pre-trained model’s capabilities and then fine-tuning its parameters to better fit the data from the specific context where it will be applied. The goal is to focus the model’s capabilities on the problem at hand. For example, the original GPT model can write fallacious, fractured, or even fanatical text because there is a lot of such text in real-world training data. However, we might want to fine-tune the model to mimic an honest, humanlike, and humane style.

To achieve this, teams at OpenAI, Google, Stanford, and others have collected thousands of examples of instruction-following dialogues that have the attributes required. For instance, when given an instruction in the input, the model should predict a response that gives a direct, correct, well-reasoned, well-written, and ethical answer to that instruction.

How is such fine-tuning done? OpenAI fine-tunes GPT on instruction-following using a combination of direct word-prediction training and reinforcement learning based on a learned policy model. However, the use of reinforcement learning is an implementation detail that not everyone uses, and it is reasonable to simply tune the model to predict words in the new data set. The basic idea is to adjust the model so that it begins with the assumption that it is working in the particular instruction-following linguistic context that we want it to be in.

The usefulness and power of the model we get in the end depends on three things:

- the pretraining data (e.g., all the world’s text);

- the fine-tuning data (e.g., exactly which examples you select for instruction-following);

- the training architecture (what computations the transformer is able to learn).

For example, if you fine-tune a model on text written by a recalcitrant 3rd grader, you will expect it to produce 3rd grade output that bickers with you. But if you fine-tune it on text demonstrating an obedient savant who can do an amazing range of difficult and useful instruction-following tasks, then you can hope it will mimic that willingness and ability to solve difficult problems. You can look at examples of instruction-following data within the Stanford Alpaca dataset, here on huggingface.

This ability to fine-tune a model to follow our explicit instructions also touches on concerns that people like Eliezer Yudowsky have long had that large-scale machine learning may end up producing systems that end up being destructive to humanity. Instrutions seem to give us a way to make models a little safer. We can train models to follow our instructions and to follow societal norms and even ethical constraints by giving lots of examples. Anthropic, in particular, has been thinking about how to encode nontrivial ethical reasoning into model fine-tuning data.

Why this might work at all is itself wondrous (and again, the subject of study in this blog). If we are genuinely interested in AI safety, it demands a deeper understanding of what is happening under the hood. But training models to follow our instructions by-example seems to work, at least on a surface level. So that is the modern program.

Retrieval methods, tool use, and secrecy.

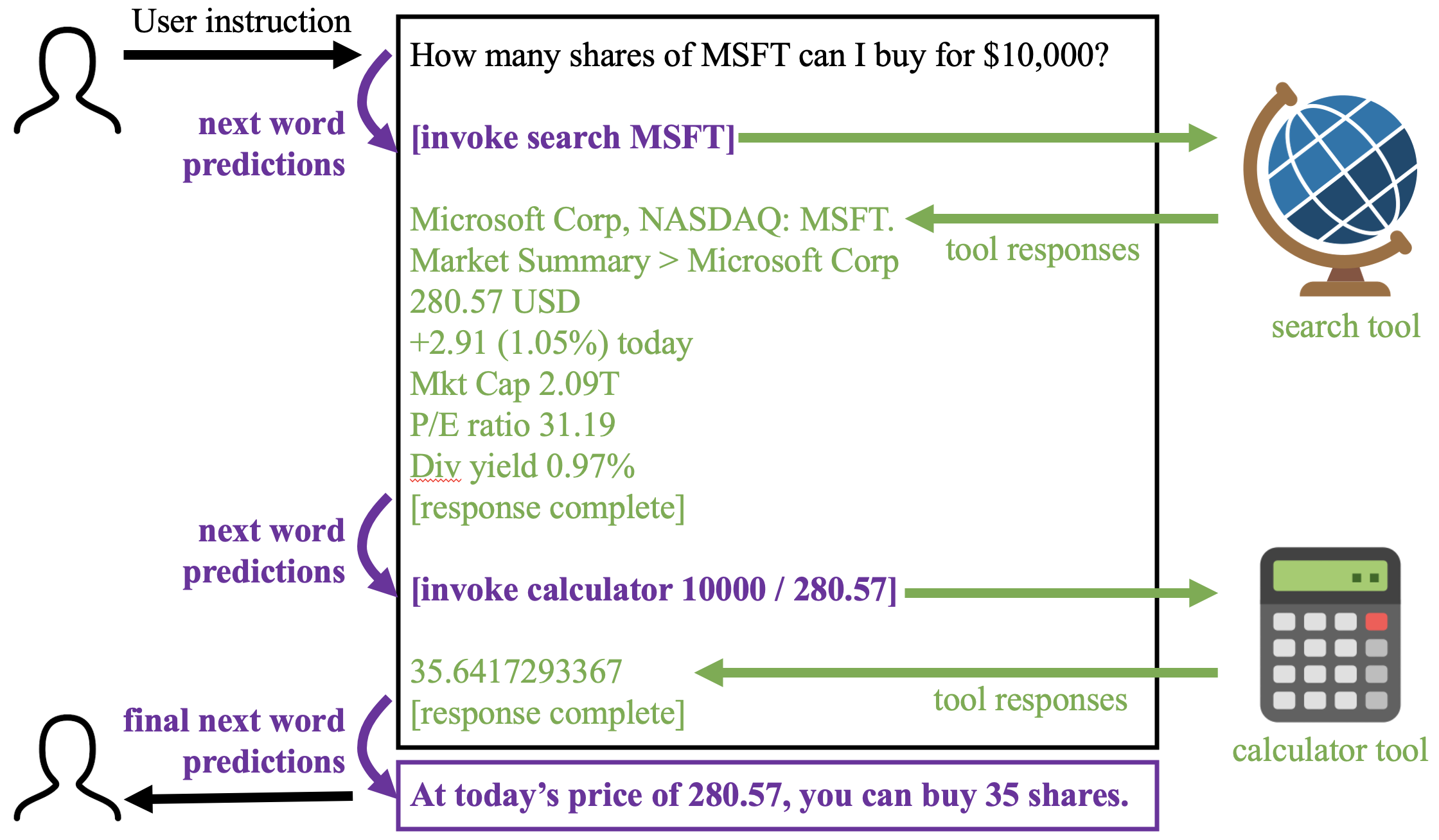

It is obvious that there is a fourth thing you might want the model to be able to depend on: tools and resources in the real world.

So you can make this fourth thing part of the fine-tuning data. For example, you could demonstrate that, as part of answering, when it would be approprate to do a Google search for X, it should output a special token sequence [invoke googlesearch X], and then it should expect to see further input that includes all the top Google search results. Or when it would be appropriate to see the contents of a web page at url U, it should say [invoke webget U] and it would be able to see the contents of the web page on the input.

Of course an ordinary GPT model might have no idea when it should be doing web searches and so on, but perhaps if we give it a few examples, or better yet we include many thousand fully-worked interactions, where we pantomime the interaction with the open web within a fine-tuning data set, then it will start to exploit this new form of interaction.

We could bake such interactions into the transformer during pre-training. Those are called “retrieval based architectures,” (e.g., see RETRO, Sebastian Borgeaud 2021), and they work. They tend to create models that do not waste all their parameters memorizing the world’s knowledge, but instead they will make requests to see different pieces of text when making predictions. But you could also add such interactions at fine-tuning time, after pretraining on ordinary word prediction. Because fine-tuning is fast and much more amenable to quick experimentation and engineering than training from scratch, that is probably what I would expect to see in practice. What you would need is a data set of thousands of worked examples of tool use.

OpenAI has not revealed the internal architecture or training methods used to create ChatGPT, but three days ago they released a new plugin architecture that suggests that tool-use has been a major part of their work on ChatGPT. You can see some examples of their plug-in architecture here.

https://platform.openai.com/docs/plugins/examples.

Using their API, you can define connections to internet tools, and chatGPT will use those tools whenever it chooses to. The natural way to interface between a language model and an eternal resource is to train fine-tune the model to emit special tokens such as [invoke tool with input X] in the output that would be hidden from the user but instead routed to the tool. To do this, one would create a dataset demonstrating such tool use, maybe by instrumenting web browsers to watch how people use online tools such as search engines, stores, calendars, etc, in practice. Or maybe by having a team of experts making REST API calls for successful interactions and encoding these as examples “tool use example” scripts.

So, in a world with many tools, how does the system decide which tool is the best one to use? Expect this type of judgment to be one of the pivotal competitive questions in coming decades.

OpenAI has not disclosed how they are training ChatGPT to choose between tools, but this could be solved in a number of ways, for example, in their tool-fine-tuning examples, they could provide text to the input of GPT that lists all the descriptions of tools, and then after that context, they could have examples of choosing the right tool from the list at an appropriate moment during conversation. After seeing a few thousand of such worked examples during fine-tuning, I would expect the model to be able to mimic generic tool use pretty well. Then the training data could be curated to exemplify behavior that OpenAI judges as most desirable.

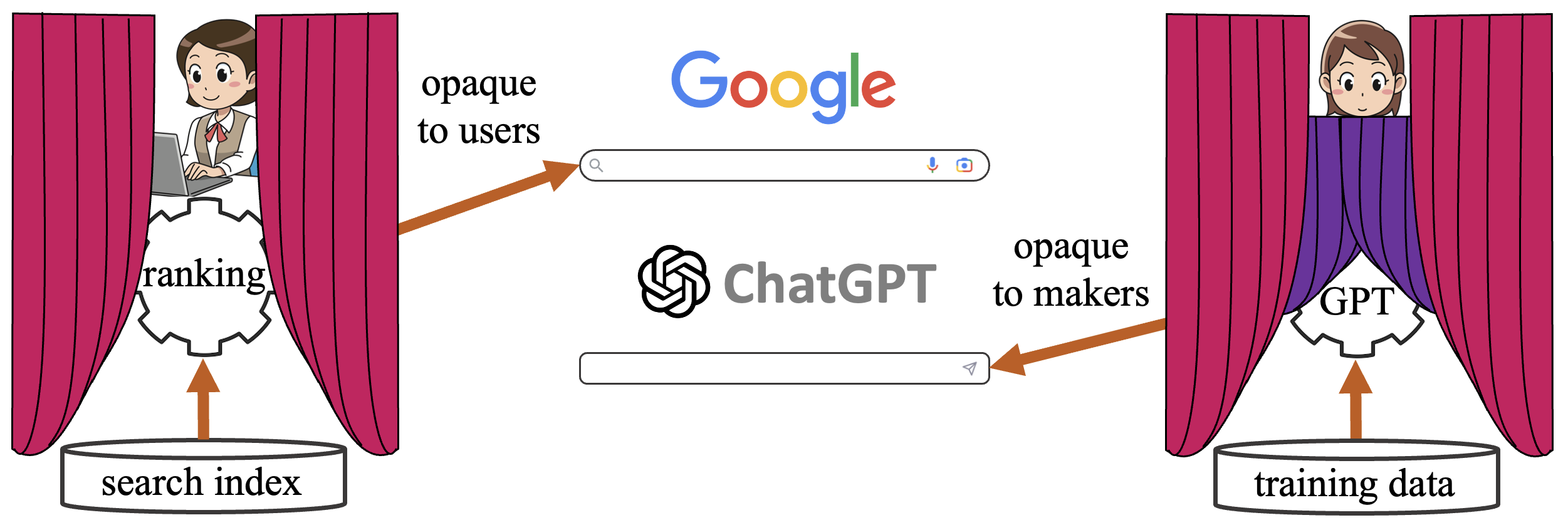

ChatGPT is doubly opaque.

We are in an interesting but concerning new era now, where the key decision-making of the algorithm is doubly opaque. First, the way that OpenAI has hooked together and trained their system is opaque to us, since their architectures and training data are all proprietary trade secrets. That is similar to how Google’s search ranking is opaque to outsiders. Google will never reveal its very clever internal methods for deciding between websites.

But now, there is a second profound issue that sparks a deeper concern. Unlike the case of Google, where company engineers can understand the search ranking system with a set of traditional debugging tools, when we are working with a massive model like GPT-3 or GPT-4, the decision-making of the model is opaque even to OpenAI themselves. When the model chooses one behavior over another, the engineers may not have any insight as to “why,” beyond the billions of tangled arithmetic operations that led to the prediction of a token.

We will train our models using billions of pretraining examples, cleverly chosen architectures, and thousands of fine-tuning examples. But then the actual algorithm that it applies is the result of a massive and opaque optimization.

What are these systems actually learning?

That is the most urgent problem facing computer science, and maybe all of science, today. Answering that question has massive economic consequences. And the question also delves into ancient questions, “what is thinking” and “what is knowledge?”

It is important to ask the question transparently and openly, and not as a trade secret.

That’s why I left Google to work on this.

Join us!